Hellenism in Gandharan Buddhism

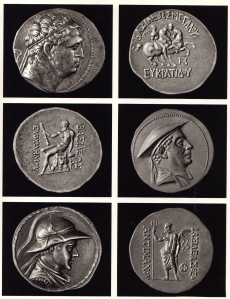

As mentioned in the previous section, early Indian Buddhist art represented the Buddha through symbols, and not in the human form. How, then, do scholars explain the evolution of Gandharan art, where the Buddha is displayed in an iconic manner? A group of scholars focused on Alexander the Great’s expedition to India and the Graeco-Bactrian kingdom that came as a result of his journey. After Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BC, Euthydemus and Demetrios (Euthydemus’s son) became prominent Graeco-Bactrian kings. Their dominance and prosperity is evident as they appear on coins found in Gandhara, and other such regions, most of which display the king wearing an elephants skin atop his head (Hallade 19). This is a clear indication of the Hellenistic impact on Gandharan society.

However, the influence of Greek art on the Gandhara School goes beyond coinage. Examples of this are provided in the following two figures:

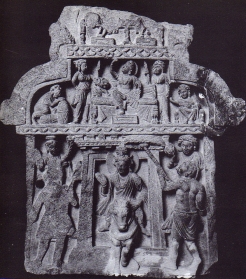

The above two images illustrate a growing theme in Gandhara, possibly borrowed from Graeco-Parthian art – an art form that also shows Hellenistic contributions. The popular theme in Parthia during this era is that of the drinking scene. In the first image, the drinking theme is depicted as is – a drinking party of men and women (Marshall 33). However, in the second image, the drinking glasses are replaced with the lotus flower. Academics speculate that the holy nature of the ‘drinking party scene’ came into question and resulted in the replacement of drinking glasses with more religiously appropriate lotus flowers (Marshall 34). Nonetheless, it is important to note that, although images illustrate a similar Greek style in terms of Greek form and posture, the sculpted characters are portrayed in local attire (Marshall 35). Moreover, scholars do recognize a further extension to Hellenistic art, whereby poses, posture, and drapery are also mimicked (Marshall 41). An example of such Hellenstic influences can be seen in the following image:

Notice that the Buddha is only distinguishable from the rest of the figures by a halo, which reflects another Greek invention. In the above image, Buddha is second from the left, the halo is present yet difficult to see. Furthermore, the Buddha’s characteristics – the small/drooping moustache, slightly pointed nose, and strongly marked cheekbones – are distinctively Greek features (Marshall 42).

Not only are stylistic features of Gandharan art similar to those in Greek sculptures, but the way in which time is displayed in a narrative Gandharan sculpture is also strikingly similar to narration in Greek pieces. In Indian art, narrative art pieces are not concerned with a chronological display, rather they are more continuous in nature with absence of spacing in-between scenes (Nehru 17). On the other hand, Classical Greek narrative art portrays single important events in time, which are presented in a sequential manner (Nehru 15). The Gandhara School of Art adopted this sequential narration from the West (Nehru 17).

The image on the left represents a prototypical Greek narrative scene. It is to be compared with the image on the right, a narrative scene from Gandhara. Notice that both images focus on single moment events with spaces in between to illustrate a break in the sequential narration. These characteristics in Gandharan art are borrowed from Classic Greek style.